Accessing Input Elements#

When dealing with complex input formats, attaching constraints can be complex, as elements can occur multiple times in a generated input. Fandango offers a few mechanisms to disambiguate these, and to specify specific contexts in which to search for elements.

Derivation Trees#

So far, we have always assumed that Fandango generates strings from the grammar. Behind the scenes, though, Fandango creates a far richer data structure - a so-called derivation tree that maintains the structure of the string and allows accessing individual elements. Every time Fandango sees a grammar rule

<symbol> ::= ...

it generates a derivation tree whose root is <symbol> and whose children are the elements of the right-hand side of the rule.

Let’s have a look at our persons.fan spec:

<start> ::= <person_name> "," <age>

<person_name> ::= <first_name> " " <last_name>

<first_name> ::= <name>

<last_name> ::= <name>

<name> ::= <ascii_uppercase_letter><ascii_lowercase_letter>+

<age> ::= <digit>+

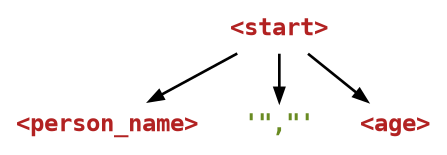

The <start> rule says

<start> ::= <person_name> "," <age>

Then, a resulting derivation tree for <start> looks like this:

As Fandango expands more and more symbols, it expands the derivation tree accordingly.

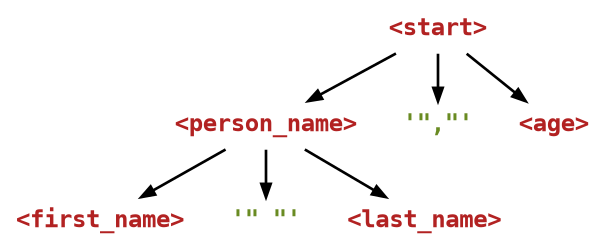

Since the grammar definition for <person_name> says

<person_name> ::= <first_name> " " <last_name>

the above derivation tree would be extended to

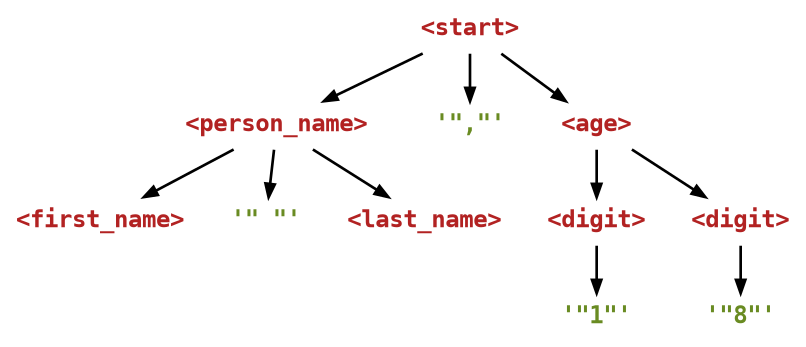

And if we next extend <age> and then <digit> based on their definitions

<age> ::= <digit>+

our tree gets to look like this:

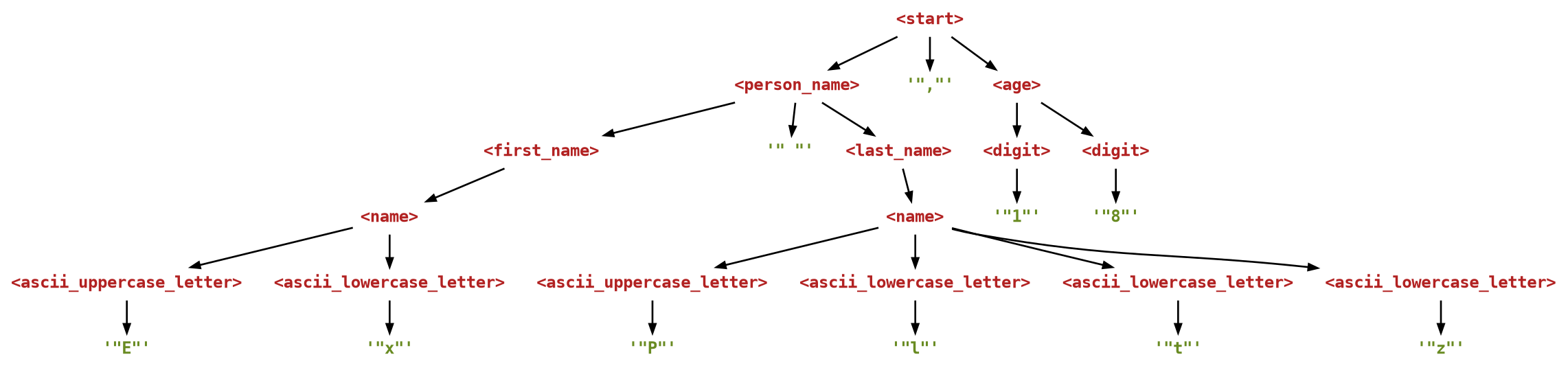

Repeating the process, it thus obtains a tree like this:

Note how the tree records the entire history of how it was created - how it was derived, actually.

To obtain a string from the tree, we traverse its children left-to-right,

ignoring all nonterminal symbols (in <...>) and considering only the terminal symbols (in quotes).

This is what we get for the above tree:

Ex Pltz,18

And this is the string Fandango produces. However, viewing the Fandango results as derivation trees allows us to access elements of the Fandango-produced strings and to express constraints on them.

Diagnosing Derivation Trees#

To examine the derivation trees that Fandango produces, use the --format=grammar output format.

This produces the output in a grammar-like format, where children are indented under their respective parents.

As an example, here is how to print a derivation tree from persons.fan:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 1 --format=grammar

<start> ::= <person_name> ',' <age> # Position 0x0000 (0); Hqwlsxsvunuqlykmguykt Yxvrkmdcyviqthymndxy,6053337261160

<person_name> ::= <first_name> ' ' <last_name> # Position 0x0001 (1); Hqwlsxsvunuqlykmguykt Yxvrkmdcyviqthymndxy

<first_name> ::= <name>

<name> ::= <ascii_uppercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> # Hqwlsxsvunuqlykmguykt

<ascii_uppercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_uppercase_letter>

<_ascii_uppercase_letter> ::= 'H' # Position 0x0002 (2)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'q' # Position 0x0003 (3)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'w' # Position 0x0004 (4)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'l' # Position 0x0005 (5)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 's' # Position 0x0006 (6)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'x' # Position 0x0007 (7)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 's' # Position 0x0008 (8)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'v' # Position 0x0009 (9)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'u' # Position 0x000a (10)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'n' # Position 0x000b (11)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'u' # Position 0x000c (12)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'q' # Position 0x000d (13)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'l' # Position 0x000e (14)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'y' # Position 0x000f (15)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'k' # Position 0x0010 (16)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'm' # Position 0x0011 (17)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'g' # Position 0x0012 (18)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'u' # Position 0x0013 (19)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'y' # Position 0x0014 (20)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'k' # Position 0x0015 (21)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 't' # Position 0x0016 (22)

<last_name> ::= <name>

<name> ::= <ascii_uppercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> <ascii_lowercase_letter> # Yxvrkmdcyviqthymndxy

<ascii_uppercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_uppercase_letter>

<_ascii_uppercase_letter> ::= 'Y' # Position 0x0017 (23)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'x' # Position 0x0018 (24)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'v' # Position 0x0019 (25)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'r' # Position 0x001a (26)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'k' # Position 0x001b (27)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'm' # Position 0x001c (28)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'd' # Position 0x001d (29)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'c' # Position 0x001e (30)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'y' # Position 0x001f (31)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'v' # Position 0x0020 (32)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'i' # Position 0x0021 (33)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'q' # Position 0x0022 (34)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 't' # Position 0x0023 (35)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'h' # Position 0x0024 (36)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'y' # Position 0x0025 (37)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'm' # Position 0x0026 (38)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'n' # Position 0x0027 (39)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'd' # Position 0x0028 (40)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'x' # Position 0x0029 (41)

<ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= <_ascii_lowercase_letter>

<_ascii_lowercase_letter> ::= 'y' # Position 0x002a (42)

<age> ::= <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> <digit> # 6053337261160

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '6' # Position 0x002b (43)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '0' # Position 0x002c (44)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '5' # Position 0x002d (45)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '3' # Position 0x002e (46)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '3' # Position 0x002f (47)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '3' # Position 0x0030 (48)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '7' # Position 0x0031 (49)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '2' # Position 0x0032 (50)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '6' # Position 0x0033 (51)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '1' # Position 0x0034 (52)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '1' # Position 0x0035 (53)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '6' # Position 0x0036 (54)

<digit> ::= <_digit>

<_digit> ::= '0' # Position 0x0037 (55)

We see how the produced derivation tree consists of a <start> symbol, whose <first_name> and <last_name> children expand into <name> and letters; the <age> symbol expands into <digit> symbols.

The comments (after #) show the individual positions into the input, as well as the values of compound symbols.

What is the full string represented by the above derivation tree?

Solution

You can find on the right-hand side of the first line.

Tip

The --format=grammar option is great for debugging, especially binary formats.

Specifying Paths#

One effect of Fandango producing derivation trees rather than “just” strings is that we can define special operators that allow us to access subtrees (or sub-elements) of the produced strings - and express constraints on them.

This is especially useful if we want constraints to apply only in specific contexts - say, as part of some element <a>, but not as part of an element <b>.

Accessing Children#

The expression <foo>[N] accesses the N-th child of <foo>, starting with zero.

If <foo> is defined in the grammar as

<foo> ::= <bar> ":" <baz>

then <foo>[0] returns the <bar> element, <foo>[1] returns ":", and <foo>[2] returns the <baz> element.

In our persons.fan derivation tree for Ex Pltz, for instance, <start>[0] would return the <person_name> element ("Ex Pltz"), and <start>[2] would return the <age> element (18).

We can use this to access elements in specific contexts.

For instance, if we want to refer to a <name> element, but only if it is the child of a <first_name> element, we can refer to it as <first_name>[0] - the first child of a <first_name> element:

<first_name> ::= <name>

Here is a constraint that makes Fandango produce first names that end with x:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 10 -c '<first_name>[0].endswith("x")'

Rrchavxroebhjx Aninpwcluehlq,70653

Wxogrbcdcxydzx Anfmu,3

Mmfmx Dhvu,979448657687252627

Hxogrbcdcxydzx Anfmu,3

Rrchavxroebhjx Aninpwcluehlq,4102843681784

Mmfmx Anfmu,3

Wxogrbcdcxydzx Dhvu,979448657687252627

Kmfmx Dhvu,979448657687252627

Mmfmx Ahvu,979448657687252627

Rrchavxroebhjx Dninpwcluehlq,70653

Tip

As in Python, you can use negative indexes to refer to the last elements.

<age>[-1], for instance, gives you the last child of an <age> subtree.

Important

While symbols act as strings in many contexts, this is where they differ.

To access the first character of a symbol <foo>, you need to explicitly convert it to a string first, as in str(<foo>)[0].

Slices#

Fandango also allows you to use Python slice syntax to access multiple children at once.

<name>[n:m] returns a new (unnamed) root which has <name>[n], <name>[n + 1], …, <name>[m - 1] as children.

This is useful, for instance, if you want to compare several children against a string:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons-faker.fan -n 10 -c '<name>[0:2] == "Ch"'

Christopher Chapman,61

Charlotte Chapman,784251204150414

Christopher Chapman,0446620

Christy Chapman,7538751

Christopher Chapman,869050093

Christy Chapman,7518751

Charlotte Chapman,44502

Christopher Chapman,24002

Charlotte Chapman,47850

Christy Chapman,7538701

Would one also be able to use <start>[0:2] == "Ch" to obtain inputs that all start with "Ch"?

Solution

No, this would not work. Remember that in derivation trees, indexes refer to children, not characters. So, according to the rule

<start> ::= <person_name> "," <age>

<start>[0] is a <person_name>, <start>[1] is a ",", and <start>[2] is an <age>.

Hence, <start>[0:2] refers to <start> itself, which cannot be "Ch".

Indeed, to have the string start with "Ch", you (again) need to convert <start> into a string first, and then access its individual characters:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons-faker.fan -n 10 -c 'str(<start>)[0:2] == "Ch"'

Charles Shepherd,32056256

Christine Esparza,371025548537289412

Charles Newman,3689864097557625506

Christopher Lewis,2199924725681583

Christine Esparza,44

Charles Newman,6032875763610171391

Christine Esparza,371025548537289418

Christopher Shepherd,2199924725681583

Charles Lewis,32056256

Christopher Lewis,2490908908613

Fandango supports the full Python slice semantics:

An omitted first index defaults to zero, so

<foo>[:2]returns the first two children.An omitted second index defaults to the size of the string being sliced, so

<foo>[2:]returns all children starting with<foo>[2].Both the first and the second index can be negative again.

Selecting Children#

Referring to children by number, as in <foo>[0], can be a bit cumbersome.

This is why in Fandango, you can also refer to elements by name.

The expression <foo>.<bar> allows accessing elements <bar> when they are a direct child of a symbol <foo>.

This requires that <bar> occurs in the grammar rule defining <foo>:

<foo> ::= ...some expansion that has <bar>...

To refer to the <name> element as a direct child of a <first_name> element, you thus write <first_name>.<name>.

This allows you to express the earlier constraint in a possibly more readable form:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 10 -c '<first_name>.<name>.endswith("x")'

Jjrllcndplfcqnhhwujox Dwh,966715729081840769

Hx Qdmseonuxq,891293089695

Cgtgeadvrbx Qhyzj,41302981855439

Crrlgdnzlmjcdjtx Dsngmzycyvnkfjh,04582660162658

Cgtgeadvrbx Qkm,41302981855439

Crrlgdnzlmjcdjtx Dsnxmzycyvnkfjh,04582660162658

Jjrllcndplfcqnhhwujox Dsngmzycyvnkfjh,04582660162658

Crrlgdnzlmjcdjtx Dwh,966715729081840769

Jjrllcndplfcqnhhwujox Fmzdmfudyhonmqfkjglyk,657

Jjrllcndplfcqnhhwujox Dwh,966715729981840769

Note

You can only access nonterminal children this way; <person_name>." " (the space in the <person_name>) gives an error.

Selecting Descendants#

Often, you want to refer to elements in a particular context set by the enclosing element. This is why in Fandango, you can also refer to descendants.

The expression <foo>..<bar> allows accessing elements <bar> when they are a descendant of a symbol <foo>.

<bar> is a descendant of <foo> if

<bar>is a child of<foo>; orone of

<foo>’s children has<bar>as a descendant.

If that sounds like a recursive definition, that is because it is.

A simpler way to think about <foo>..<bar> may be “All <bar>s that occur within <foo>”.

Let us take a look at some rules in our persons.fan example:

<first_name> ::= <name>

<last_name> ::= <name>

<name> ::= <ascii_uppercase_letter><ascii_lowercase_letter>+

<ascii_uppercase_letter> ::= "A" | "B" | "C" | ... | "Z"

To refer to all <ascii_uppercase_letter> element as descendant of a <first_name> element, you thus write <first_name>..<ascii_uppercase_letter>.

Hence, to make all uppercase letters X, but only as part of a first name, you may write

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 10 -c '<first_name>..<ascii_uppercase_letter> == "X"'

Xsozwqhzjjcjwgtwih Velhkqyfim,179977124048

Xipjteisag Qjknpisctyuqizghu,061

Xlhgtdbnfgycdvwwd Oowyje,91

Xiwztwiqwswauxbmabsei Jrtyacvcbbxxrdr,26419929

Xzlhzmdp Vgc,367230259609

Xgchsx Sefdrdbufljluqpp,177384565939377

Xtduvgksnnoszdzjxy Jkwiddjkkzmwxxcmntwh,41

Xmvxgwnnwsotcvd Obuit,24423225282

Xmjqwjxd Pzoew,98576355402596270397

Xlwbyzk Mtcohhfwgplemiifa,27

Chains#

You can freely combine [], ., and .. into chains that select subtrees.

What would the expression <start>[0].<last_name>..<ascii_lowercase_letter> refer to, for instance?

Solution

This is easy:

<start>[0]is the first element of start, hence a<person_name>..<last_name>refers to the child of type<last_name>..<ascii_lowercase_letter>refers to all descendants of type<ascii_lowercase_letter>

Let’s use this in a constraint:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 10 -c '<start>[0].<last_name>..<ascii_lowercase_letter> == "x"'

Eeslwdgzgvbqmdaxkwiqx Hxxxxxxxxxxxxxx,81808977

Yjbpocdjdhqnzesvqiji Yxxxxxxx,0443367

Mwhsojx Ixxxxxxxx,22221

Rvyqrltaosjrmnvv Txxxxxxxxxxxxx,336167

Wgxsklewtbnluv Fxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx,912166575100609160

Fbivniqytpjo Vxxxxxxxxxx,1765666990

Afuaimsafhfxzvar Pxxxxxxxxxxx,01989

Myudoeacbwx Bxxxxx,2030

Zxpftgb Cxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx,430503675740525867

Pihxhamkwdl Dxxxxx,9470812421226667214

Quantifiers#

By default, whenever you use a symbol <foo> in a constraint, this constraint applies to all occurrences of <foo> in the produced output string.

For your purposes, though, one such instance already may suffice.

This is why Fandango allows expressing quantification in constraints.

Star Expressions#

In Fandango, you can prefix an element with * to obtain a collection of all these elements within an individual string.

Hence, *<name> is a collection of all <name> elements within the generated string.

This syntax can be used in a variety of ways.

For instance, we can have a constraint check whether a particular element is in the collection:

"Pablo" in *<name>

This constraint evaluates to True if any of the values in *<name> (= one of the two <name> elements) is equal to "Pablo".

*-expressions are mostly useful in quantifiers, which we discuss below.

Existential Quantification#

To express that within a particular scope, at least one instance of a symbol must satisfy a constraint, use a *-expression in combination with any():

any(CONSTRAINT for ELEM in *SCOPE)

where

SCOPEis a nonterminal (e.g.<age>);ELEMis a Python variable; andCONSTRAINTis a constraint overELEM

Hence, the expression

any(n.startswith("A") for n in *<name>)

ensures there is at least one element <name> that starts with an “A”:

Let us decompose this expression for a moment:

The expression

for n in *<name>lets Python iterate over*<name>(all<name>objects within a person)…… and evaluate

n.startswith("A")for each of them, resulting in a collection of Boolean values.The Python function

any(list)returnsTrueif at least one element inlistis True.

So, what we get is existential quantification:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 10 -c 'any(n.startswith("A") for n in *<name>)'

Kc Anxspjbbdftmphr,571859227740866

Axkdvhfyyngymeg Xxvxmyvidpre,67646

Emcvexfhqsterhfsgc Aejrwbrzqkxlkidqbtvtr,1684221095

Arey Fdifgdltjmatxketdk,6537548

Atwy Horsqm,92030

Azgl Ae,315667775072526

Emcvexfhqsterhfsgc Aejrwbrzqkxlkidqbtvtr,04951342608600206

Emcvexfhqsterhfsgc Aejrwbrzqkxlkidqbtvtr,8992490011

Emcvexfhqsterhfsgc Aejrwbrzqkxlkidqbtvtr,7618635976811

Axkdvhfyyngymeg Xxvxmyvidpre,883308916180059

Universal Quantification#

Where there are existential quantifiers, there also are universal quantifiers.

Here we use the Python all() function; all(list) evaluates to True only if all elements in list are True.

We use a *-expression in combination with all():

all(CONSTRAINT for ELEM in *SCOPE)

Hence, the expression

all(c == "a" for c in *<first_name>..<ascii_lowercase_letter>)

ensures that all sub-elements <ascii_lowercase_letter> in <first_name> have the value “a”.

Again, let us decompose this expression:

The expression

for c in *<first_name>..<ascii_lowercase_letter>lets Python iterate over all<ascii_lowercase_letter>objects within<first_name>…… and evaluate

c == "a"for each of them, resulting in a collection of Boolean values.The Python function

all(list)returnsTrueif all elements inlistare True.

So, what we get is universal quantification:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 10 -c 'all(c == "a" for c in *<first_name>..<ascii_lowercase_letter>)'

Qaaaaaaaaaaa Et,303510561470929

Iaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa Vcecgh,6018747232255

Oaaaaaaa Upib,43426714004

Saaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa Izbnblcylocaft,35443592

Waaaaaaaaaaaa Vmlwjh,5691445100

Laaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa Ovosnwiixzrqjk,421732557

Baaaaaaaaaa Cimvmcn,6976762726528

Faaaaaaaaaaaaaa Ymfcpcqncbtmfxznppqjh,940534076

Yaaaa Baiteogpwgdmesynwlm,536480248416424985

Iaa Fozujzrj,41682735

By default, all symbols are universally quantified within <start>, so a dedicated universal quantifier is only needed if you want to limit the scope to some sub-element.

This is what we do here with <first_name>..<ascii_lowercase_letter>, limiting the scope to <first_name>.

Given the default universal quantification, you can actually achieve the same effect as above without all() and without a *. How?

Solution

You can access all <ascii_lowercase_letter> elements within <first_name> directly:

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 10 -c '<first_name>..<ascii_lowercase_letter> == "a"'

Old-Style Quantifiers#

Prior to version 1.0, Fandango supported another style of quantifiers:

The expression

forall SYMBOL in EXPRESSION: CONSTRAINTis equivalent toall(CONSTRAINT for ELEM in *EXPRESSION: )The expression

exists SYMBOL in EXPRESSION: CONSTRAINTis equivalent toany(CONSTRAINT for ELEM in *EXPRESSION: )

with SYMBOL being a symbol (in <...>, so not a Python object) which can be referred to in CONSTRAINT.

To express that at least one letter in <first_name> should be 'a', write

exists <c> in <first_name>: str(<c>) == 'a'

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 5 -c 'exists <c> in <ascii_lowercase_letter>: str(<c>) == "a"'

Dvsnscyjbpxugrsbhvwm Evitatizwvxlld,906155681122

Daaasaaaaaaaaasbavaa Evaaatiawvxala,906155681122

Xaaa Jaaaavaaaa,34733328571731031277

Jtdjyeualqelc Uiergonrpmv,243586587

Jaaaaaaaaaela Uaeaaaaraaa,243586587

$ fandango fuzz -f persons.fan -n 5 -c 'forall <c> in <ascii_lowercase_letter>: str(<c>) == "a"'

Ra Daaaaaaaaaaaaaa,1616086849508707135

Aaaaaa Baaaa,502712

Ka Maaaa,156786076

Ba Baaaaa,9350746427

Laa Gaaa,67495726671302515324

Deprecated since version 1.0: Old-style quantifiers will be deprecated in a future Fandango version. Use all() and any() instead.